Start Hacking with React

A Simple Example

@jsx React.DOMenables XML syntax known asjsx.- The

Reactmodule allows for creation and rendering of React components. msgis a React component instance, constructed using XML syntax.React.renderComponentrenders the react content into the document.

Behind the Scenes

Fig 1: Simple Example of React Usage

/**

* @jsx React.DOM

*/

var React = require('React');

var msg =

<div class="outerDiv">

<span>hello</span>

</div>;

React.renderComponent(msg, document.getElementById('someId'));

Behind the Scenes

The previous example was very straightforward except for the use of

XML syntax. The inclusion of @jsx React.DOM accomplishes

two things.

- Tells the build system to compile XML syntax into standard javascript function calls.

-

Ensures that

divandspanare functions that are in scope. In fact, all standard DOM tags (such asimgandulare also treated this way).

Obviously, javascript isn't the most attractive way to specify

declarative structures. The XML syntax will be used for the

remainder of this tutorial. Additionally, require calls and calls to

React.renderComponent will be ommited from

examples.

Fig 2: Example of compiler output

/**

* @jsx React.DOM

*/

var React = require('React');

var div = React.DOM.div;

var span = React.DOM.span;

var msg =

div({

className:"outerDiv",

children: [

span({

children: ['hello']

})

]

});

React.renderComponent(msg, document.getElementById('someId'));

Mobile Development

If developing for mobile, ensure that React is listening to touch events before performing rendering. This only needs to be done once. Everything else is exactly as it would be on desktop.Fig 2.5: Supporting mobile

React.initializeTouchEvents(true);

React.renderComponent(yourComponent, document.getElementById('someId'));

JSX Development Environment

- Vim already supports the

jsxsyntax out of the box. - If you prefer Emacs, JS2 mode works well.

- For Sublime Text, you can use the

excellent Facelime

tools which adds syntax highlighting and inline editor linting of

jsx. - Arc lint correctly supports

jsxsyntax.

Types of Components application building blocks

DOM Components such as div and span.

DOM components are always in scope when including @jsx

React.DOM in the first docblock comment. All DOM components

support children in addition to standard DOM

attributes class, href, etc. The only thing to

remember, is that DOM attributes should be expressed in camelCase (onClick).

Fig 4: DOM Component attributes

var fbUrl = "www.facebook.com";

var btn = <a href={fbUrl} class="butButton"> Visit Facebook </a>;

Composite Components such as Typeahead and LeftNav

ReactCompositeComponents are "custom" components.

Composite components are not automatically "in scope" like

ReactDOMComponents. The tag name will need to be

defined as a variable in the scope. By convention, each

ReactCompositeComponent is a commonJS module.

Remember: Composite components must be in scope before use.

Fig 5: Usage of COMPOSITE COMPONENT

// Suppose Typeahead is an instnace of ReactCompositeComponent

var Typeahead = require('Typeahead');

// Typeahead has chosen to accept a "selected" attribute

// and children.

var myTypeahead=

<Typeahead selected="jordanjcw" >

{something.dataset}

</Typeahead>;

Let's Build a Component from scratch

The following tutorial shows you how to define a new component type

called LikeToggler.

The LikeToggler will render an image and allow the user to

toggle the like status on the image. See Image 1 to the right for a

screenshot of the final result.

To create a new component type, we must specify:

- The structure of the component - what is it composed of, and how it should be rendered.

- How it encapsulates state, and how that state changes over time.

- The way in which user interactions may influence state changes.

Note: React favors composition over inheritance as a means of abstraction.

Image 1: Final Result

1. Begin the tutorial

All of the plumbing for this tutorial has been set up for you in www/trunk. Simply edit the main tutorial javascript file and refresh your browser. (See Figure 6 to the right).

Fig 6: Editing the tutorial

vim ~/www/html/js/components/ReactTutorial/ReactTutorial.js Open http://yourSandbox.facebook.com/intern/reacttutorial

2. A New Component Shell

Here, we create a new component called LikeToggler by

making a call to React.createClass. We pass a

javascript object that describes the methods to include in the new

class. render is the most important method, and is the

only one required. It describes the structure of your

component.

Remember: render should never have side effects.

Remember:

When returning jsx blocks, parenthesis guard

against ASI.

Fig 7: basic component definition

var LikeToggler = React.createClass({

render: function() {

return (

<div>

Welcome to the tutorial. Implement LikeToggler here!

</div>

);

}

});

3. Add Richer Structure

Here, we've added a header component and a picture of Boo. We've also placed a class on the outermost div to give the component some style. In your tutorial file, change yourrender

function to match Figure 8.

Fig 8: Richer structure

var LikeToggler = React.createClass({

render: function() {

return (

<div class="LikeToggler">

<h5>Toggle your like.</h5>

<img src="https://graph.facebook.com/boo/picture" />

</div>

);

}

});

4. Add Statefulness

Let's make our app interactive! We'll allow the user to "Like" Boo through our component's interface. In order to do so, we'll want to track that state in our component internally.

Add a method calledgetInitialState to your component.

getInitialState should return a javascript object that

represents your component's initial state. We'll return an object

with likes set to false to indicate that

the user does not initially like Boo.

Fig 9: Beginning statefulness

var LikeToggler = React.createClass({

getInitialState: function() { // <--New method here

return {likes: false};

},

render: function() {

return (

<div class="LikeToggler">

<h5>Toggle your like.</h5>

<img src="https://graph.facebook.com/boo/picture" />

</div>

);

}

});

5. Set Up User Interactions.

- All DOM components support attributes and event handlers just as you would expect (but are specified in the camelCase form).

-

Add a new like toggler

spanin your rendered output. -

Add a new

divin your rendered output to display the current like status. -

Add a new member function that will handle the click on that new

like toggler. Call this method

doToggle. -

Set the

onClickattribute of thespanto be the new member. -

Place an alert inside of the

doTogglehandler to confirm that your click is wired up correctly.

Remember: Always specify DOM attributes in their camelCase form.

Fig 10: Setting up user interactions

var LikeToggler = React.createClass({

getInitialState: function() {

return {likes: false};

},

doToggle: function(event) {

// What shall we do here?

},

render: function() {

return (

<div class="LikeToggler">

<h5>Toggle your like.</h5>

<img src="https://graph.facebook.com/boo/picture" />

<div class="btn" onClick={this.doToggle}>

Like Boo

</div>

<div></div>

</div>

);

}

});

6. Change State.

We need to accomplish the following when the user clicks.

- Toggle our internal state field's

likesfield. - Change the content of the toggler

divfrom "Like Boo" to "Unlike Boo" - Change the content of the

spanfrom empty to "You like this."

You might be tempted to search for the DOM nodes whos content you

wish to change, and force them to change. However, React provides a

more powerful abstraction to help you express the dynamics of changing

content over time. In react, we change our state fields via a call to

this.setState. Then, we express render

as a function of this.state at all points in time

- for an arbitrary state. Nothing else is needed!

Here's how that plays out in our example:

First, We set our next state's likes field to an

inversion/toggle of our current likes (Line 8).

Then, we make our like toggler button's content is an expression

that is a function or an arbitrary state:

<div class="btn" onClick={this.doToggle}>

{this.state.likes ? 'Unlike Boo' : 'Like Boo'}

</div>

Finally, we do the same with the span's content

<span>{this.state.likes ? 'You Like This.' : ''}</span>

React guarantees that when state is updated, these expressions

will be reevaluated and the underlying DOM structures will be reconciled.

To be clear, you can put any expression in terms of

this.state inside of render. There are

essentially no limitations. Consider the

render function to be a constraint that you specify

and that React will always satisfy.

Fig 11: Changing State

var LikeToggler = React.createClass({

getInitialState: function() {

return {likes: false};

},

doToggle: function(event) {

this.setState({likes: !this.state.likes});

},

render: function() {

return (

<div class="LikeToggler">

<h5>Toggle your like.</h5>

<img src="https://graph.facebook.com/boo/picture" />

<span>{this.state.likes ? 'You Like This.' : ''}</span>

<div class="btn" onClick={this.doToggle}>

{this.state.likes ? 'Unlike Boo' : 'Like Boo'}

</div>

</div>

);

}

});

7. Add attributes or props

There's something lacking from our LikeToggler

component. Components such as div and span

accept attributes (such as href and

class), but currently, our component is instantiated as

follows, without attributes:

var myLikeToggler = <LikeToggler />;

Now suppose we want to control the entity being liked.

var myLikeToggler =

<LikeToggler

name="Boo"

imgSrc="http://graph.facebook.com/boo/picture"

/>;

This is extremely easy to do! Inside of the render

method, all attributes are accessible through a special member called

this.props. See the Figure 12 for the complete component.

It's worth taking a close look at the last span's

content. Recognize how the content depends on two separate pieces of

data, from two completely different locations (props

and state). Any time either of these data

change, the content of that span will always be

reconciled to the expression specified.

<div class="btn" onClick={this.doToggle}>

{(this.state.likes ? 'Unlike ' : 'Like ') + this.props.name}

</div>

Fig 12: Supporting Attributes

var LikeToggler = React.createClass({

getInitialState: function() {

return {likes: false};

},

doToggle: function(event) {

this.setState({likes: !this.state.likes});

},

render: function() {

return (

<div class="LikeToggler">

<h5>Toggle your like.</h5>

<img src={this.props.imgSrc} />

<span>{this.state.likes ? 'You Like This.' : ''}</span>

<div class="btn" onClick={this.doToggle}>

{(this.state.likes ? 'Unlike ' : 'Like ') + this.props.name}

</div>

</div>

);

}

});

Properties and State ownership of information

Note: The terms attributes and props used interchangably.

Ownership:

When you look at render, anywhere you see tags

<...> there exists an implication of "ownership".

Meaning that whatever instance renders, also "owns"

those components that are rendered. For example, in Figure 13, we

define a new component type LikeTogglerWrapper that is

composed of the LikeToggler that we previously

defined.

The LikeTogglerWrapper instance clearly owns the

LikeToggler component. The

LikeTogglerWrapper is only thing thing that determines

the props (or attributes) of the

LikeToggler. Furthermore, it is the only thing that

determines its very existence.

Fig 13: new component

var LikeTogglerWrapper = React.createClass({

render: function() {

return (

<LikeToggler

imgSrc="https://graph.facebook.com//picture"

name="jwalke"

/>

);

}

});

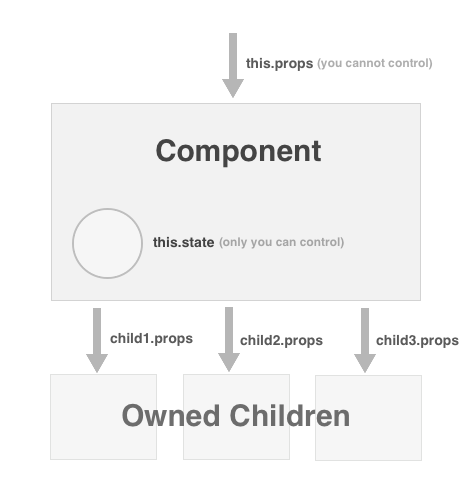

Control Of Information:

Clearly, our new component is somehow "in charge" of the

LikeToggler, so it makes sense to use the term "owner".

However, there's still one thing it's not in charge of - the

internal state of the LikeToggler.

state and props are both simple packages

of information, but they are distinct in one critical aspect

- control.

-

You control your

this.state. You are the only one that should ever updatethis.state. You never need to ask permission to update your own state because you are in control of it. -

You do not control your

this.props. Your props are controlled by the same entity that instantiated you - that is to say that yourthis.propsare controlled by your owner. Therefore, you should never update your ownthis.props.

The description of this.state

describes traditional encapsulation. But the description of

this.props is less familiar. We've described

this.props as public, but in a more restricted way than

in traditional OO design. Our props can be controlled from outside

of our component instance, because they can only be controlled from

outside of our component instance, by the owner of us. See

Figure 14 for an illustration of data flow, ownerhip and control.

These two conventions ensure that all data in the system has a single owner. If you wish to control information that you do not own, you must find a way to inform the owner of that information that you wish to change it. In other programming paradigms, these authoritatively owned packages of information may be refered to as models.

Remember:

A component instance must be the only one to update its own

this.state via a call to

this.setState({..}) and nothing else should update

its this.state.

Remember:

A component must never update its own this.props. Only

a component's "owner" (or the Reactive system) should ever

update its props.

Streams:

Examine Figure 14. It helps to think of this.props and

this.state as streams of information that your

render function operates on in order to return your

component's structure. render always

sees the freshest values of these streams. You do not need to

perform any setup to make this happen. You do not need to subscribe

to any changes. The React core makes sure that

render correctly describes your component's structure

whenever this.props or this.state may have

changed.

Flow Of Information:

We said that render always "sees the freshest values"

of this.props and this.state, but how does

this

happen? In particular, how does a component always see the freshest

values of this.props? If a component cannot update its

own this.props, then who does? The answer is that

changes to this.props will be the result of a call to

setState() at a higher level in the component

hierarchy. From the point of state update, the reactive system will

ensure that the component subtree is brought up to date by updating

the props of components below it in the hierarchy.

There are some exceptional cases, where it doesn't make sense to

merely rely on state changes to update props, but those cases are

rare. In those cases, React allows a way to attach a reference

handle to individual components returned from render

and to directly tell that component to update its props, bypassing

the standard reactive data flow. In doing so, we're not violating

the rules mentioned above. The component that specifies the

reference handles, and invokes `updateProps` is the rightful "owner"

of the referenced component and has full authority to update the

props directly.

Note: This will be further documented in a new tutorial section discussing "refs" (not yet written).

Fig 14: Control of information

Recap memorize this

-

Require other Composite Components by

requireing them. DOM components (such as<div />) are always in scope and do not need to berequired. -

DOM components support the familiar attributes, but in camelCase form (such as

onClick). -

Use

React.createClassto create a new custom component class. -

Specify the visual structure of your component in

renderas a function of an arbitrarythis.stateandthis.props. -

Inside of

render, you observe attributes by referencingthis.props.attributeName. -

Inside of

render, you observe internal state by referencingthis.states.stateFieldName. -

renderalways sees the most up-to-date values forthis.stateandthis.props. - Render should never have side effects.

-

Perform state updates via calls to

this.setState({...}). -

Only you may update your

this.state. -

You may never update your own

this.props. -

this.stateshould only ever contain serializable data (think "JSON") and you should never stuff react component instances intothis.state.